Shared Shores, Shared Futures: Sailing the Tide of Dugong Conservation

Written By Sweta Balasubramanian Iyer

My journey into dugong conservation began with the Wildlife Institute of India and unfolded into a rich tapestry of challenges, learning, and deep human connections. It started with narrating the significance of this elusive marine mammal with local fishing communities along Palk Bay-Gulf of Mannar, Southern coast of India—explaining how dugongs subtly contribute to their livelihood and survival, often through heartfelt, face-to-face conversations. My kick-start day in the field was nothing short of a revelation, unfolding as dawn broke over the organized chaos of a bustling fish market, where I found myself engulfed by throngs of people hustling to buy or sell their catch, while I stood still, absorbing it all in. My presence did not go unnoticed, as fisherwomen were particularly annoyed with me requesting measurements, species identifications, the prices, etc., among all the chaos without making any purchases. Yet, amidst the irritation, there were moments of warmth. Some women, intrigued by my work, generously shared their knowledge and even offered me fish—despite my vegetarian preferences.

I quickly learned building trust with the fishing community demanded patience and empathy, especially in this seascape where fisherwomen are central to the socio-economic fabric of the communities. Engaging with them was a learning curve—from understanding their daily schedules to finding the right moments to initiate conversations. While few were receptive, others dismissed us, finding our efforts intrusive—a humbling reminder of the complexities of grassroots outreach. I eventually understood that this deep skepticism among fisherfolk came from a long history of researchers who arrived, conducted surveys, took pictures, made promises and then disappeared—lacking any genuine connection or shared vision for their upliftment, lest offering any tangible outcomes. I realised that meaningful engagement arises from demonstrating conservation’s long-term value, not financial incentives, which often distort data. Trust built through honest dialogue fostered accurate insights and lasting collaboration.

The turning point came when I joined their routines—talking during breaks, helping in quiet hours, giving an ear to their voices transformed our relationship. Tired and wary after long hours at sea, the fishermen needed a deferential approach. Joining them during net cleaning, showing up at village meetings, and offering small gestures slowly built trust. Everyone wants to be heard—not just about work, but about their struggles, their families, and the quiet victories that shape their lives. They simply needed someone to listen. Slowly, they began opening up: sharing dugong sightings, weather patterns, and even joining awareness programs with their children. I had the privilege of connecting with people from all walks of life—different faiths, castes, creed, and cultures, as well as diverse linguistic groups. Despite their differences, they united in their shared identity as fishers. Through years of engagement, I never once felt discriminated against based on gender or caste. Instead, they welcomed me into their homes and temples, ensuring I always had food during festivities, even if they found my vegetarianism amusing!

Eventually, the community became a second family to me. Helping them through trainings, alternative livelihoods, or connecting them with NGOs and government support systems felt like a human responsibility and not just my research role. We eventually launched scholarships for fisher children and offered honorariums to fishers helping protect dugongs—a task easier said than done, given that these gentle giants weigh over 300 kg and measure 2-3 meters long. What started as a small recognition event, has now evolved into a prestigious, government-backed celebration of community-led conservation.

I was fortunate to learn from seasoned fishers, the true guardians of this region, whose traditional knowledge of the ocean, weather, and marine life was unparalleled. Their tales of dolphin pods swimming alongside their boats, manta rays gliding beneath them, and dugong courtship displays sounded like scenes from a nature documentary, akin to Tamil Nadu's very own David Attenborough narrations. Encouraging kids to ask their elders about dugong sightings uncovered a wealth of traditional knowledge, from stories of dugong migrations to firsthand observations of their behaviors. Some of the most poignant stories came from fishers who spoke of mother dugongs crying as their calves became entangled in nets. Many recalled rescuing and releasing the young, believing the mother’s gaze held gratitude and would remember with kindness who spared them harm.

The most intriguing tradition was of a small dargah village that worshipped a resident dugong, protecting it for decades and passing down this practice across generations, an exemplary of community-led conservation wherein unwavering respect ensured the animal’s peaceful survival. Nevertheless, older generations expressed sadness at the decline in dugong numbers, linking it to declining fish stocks and environmental degradation. Women, often the unseen force behind conservation, became pivotal changemakers, linking dugong protection to livelihoods, shared maternal bonds, advocating within homes and monitoring illegal activities.

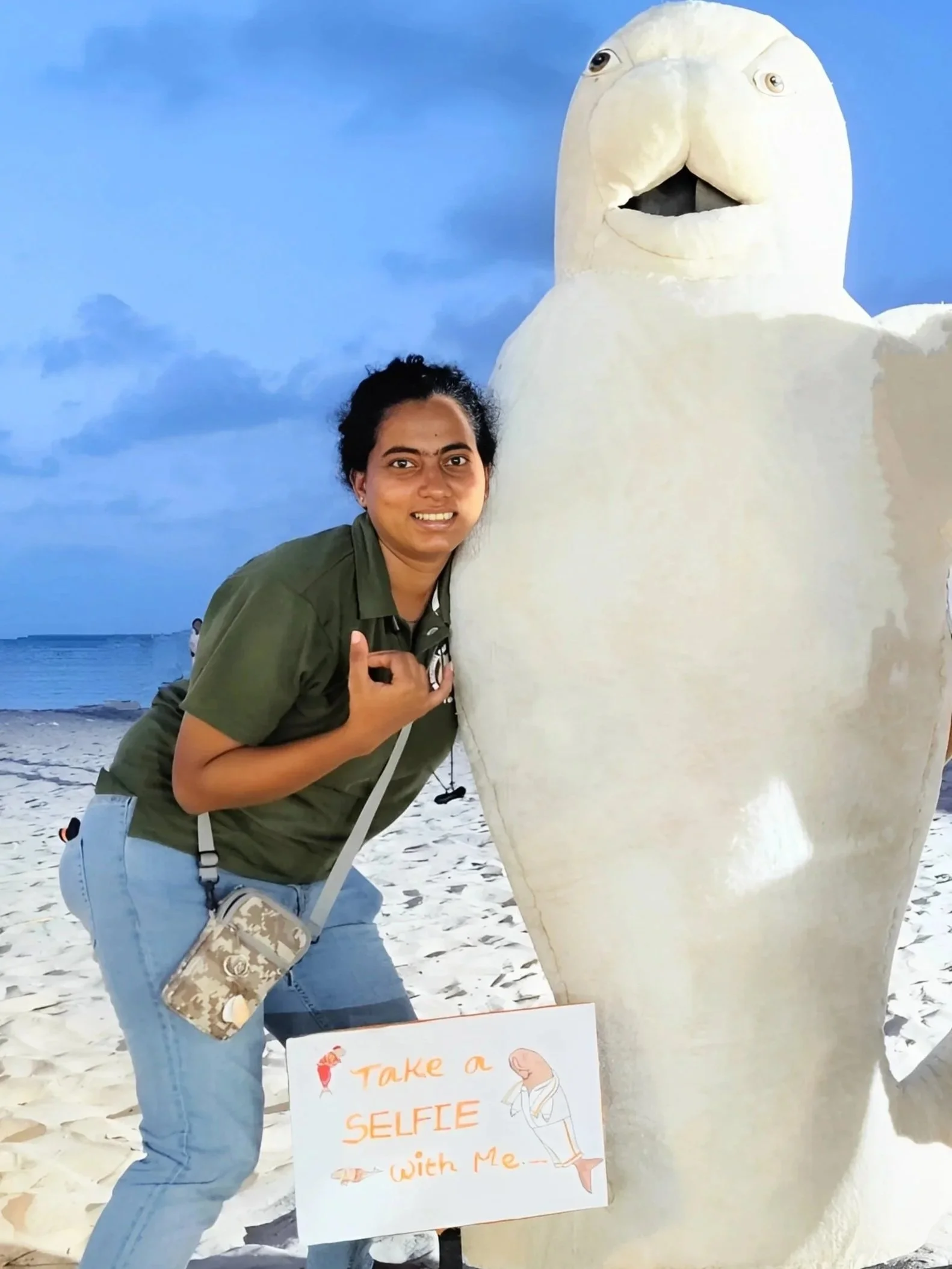

Conservation was not just about protecting a species; it was about ensuring that people, nature, and livelihoods coexisted sustainably. While progress seemed slow, small changes accumulated over time. From a single rescued dugong to a full-fledged government recognition program, from sceptical fishers to community-led conservation, and bare school walls now featuring paintings of dugongs in their ecosystems—this journey has shown me that even the smallest efforts can ripple into something remarkable.

The most striking part of my experience was witnessing the power of unity within the community. From rescuing dugongs to confronting illegal trawlers and reporting poachers, their collective action was transformative. In one case, a village detained a trawler crew that had crossed into their waters, demanding justice after earlier complaints were ignored. Instead of resorting to retaliation, they entrusted me to take their concerns to higher authorities, a powerful testament to their faith in our work.

This journey is not just about the dugong—it is about the people who share its shores. Blending scientific research with local traditions, I glimpsed the possibility where conservation is not imposed but lived. This was not only about saving an endangered species but about reimagining a world where communities and nature thrive together.

Sweta Balasubramanian Iyer

Sweta Balasubramanian Iyer is a wildlife ecologist with over seven years of experience in wildlife and marine mammal conservation across India. As a Senior Project Associate at the Wildlife Institute of India under the CAMPA–Dugong Recovery Program, she integrates field research with community-driven conservation, while studying heavy metal accumulation in dugongs. Fluent in several Indian languages, Sweta builds strong connections with coastal communities, blending science and traditional knowledge to protect endangered species and their habitats. Holding an M.Sc. in Zoology from Gujarat University, she has contributed to peer-reviewed research and awareness initiatives promoting marine ecosystem conservation and biodiversity stewardship.